The Political Economy of Mobile Screen Geographies

One of students recently emailed me about the Yo App. Like many people (including the “The Colbert Report”), she was not at first terribly impressed with its seemingly simple functionality of sending you push notifications. Yet, then it began to “make sense” to her. As she pointed out, Yo works by sending you alerts on anything the could range from how long it will be until Mom gets home in today’s traffic and you have to really stop playing W.O.W. to when the muffins come out at your favorite bakery.

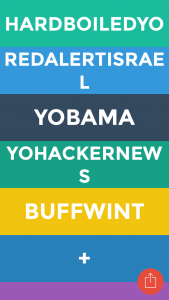

Take note: I said “could.” For now there is a limited index or you need to code your own. My chosen Yo notifications? Yo will now tell me when it is snowing in Buffalo, there is an incoming missile anywhere near the State of Israel, President Obama releases a new executive order, a post on Hacker News gets over 500 positive votes, or my hard boiled egg is done (look left). But that isn’t what interests me about this multi-million dollar venture capital funded app.

What interests me is the geography and temporality of the mobile screen and how political economies play out upon it and in it. Yes, I need to walk you through these ideas. First let’s talk space and time, then we’ll get to the politic and economy of it.

Much like the spatiotemporality of apps like Candy Crush and Farmville, Yo likes to mess with you. What I mean by this is that Candy Crush makes you wait 30 minutes to get another life to continue to play with. You can have no more than 5 lives at any time. While there are workarounds to this way of play, most people I know wait for more lives. (Obviously, Yo will have a notification that your lives have refilled. Or one would hope.) Similarly, apps like Farmville on Facebook require that you log in to the game and gather your crops at certain appointed times (Yo, are you reading this?) in order to not lose your crop and the game, or even your family, sanity, and livelihood. With Farmville, your crops may come up every half hour. In both Candy Crush and Farmville, you have to come back to this appointed space of your screen–mobile or tablet for the former and usually tablet or desktop for the latter–which could be every 30 minutes or then 2 hours, etc., to maximize play or win, respectively. As a result, people spend a great deal of time waiting to play rather than actually playing. In this moment of the attention economy, it’s waiting to get your turn on the ride at the amusement park that gets you more riled up than actually riding it.

But what is Yo’s version of messing with the space and time of your day? Push notifications and user histories don’t save to the app. Your mobile device does keep a history of notifications but Yo, all on its lonesome, is timeless. You need to be paying, sigh, attention to have at them. Small, short, and “Yo From JGIESEKING” as they may be, the app itself keeps no sense on ongoing time for you. That means that egg may have boiled, Obama may have created world peace, and there is a blizzard in Buffalo but Yo will keep no record for me to attend to. These days with these apps you need to be riled up and looking, looking, looking. Or you may miss it! Ai yah.

My first argument is that when using Yo and other apps, developers grab our interest by manipulating how space and time operate upon us rather than are produced at our own discretion.

Now we can get to that very important part of the political economy within. Christopher Mims, writing this weekend for the Wall Street Journal, said:

Here’s why Yo is important: Yo provides any person, business or Web service direct access to the notifications tray of your smartphone. Every time we glance at our phones, these are the alerts we see on our lock screens, and they also interrupt us whenever we’re doing anything else on our phones. Alerts, or so-called push notifications, are the most valuable property in the entire media universe, considering how often the average smartphone owner glances at his or her phone. [my emphasis]

What jumps out at me is this: the “most valuable property in the entire media universe” of a 4in diagonal screen (said the iPhone5s owner) is a push notification. How striking and how well said. But, in fact, I suggest that the most valuable property is the screen itself.

Say what? Okay, follow this line of thought. Around half of the people in the world are estimated to have smart phones. As Jan Chipchase, the so-called anthropologist of mobile phones / very well paid senior researcher for Nokia / expert TEDx Talk giver pointed out, people around the world leave their house, at a minimum, with their keys, their wallet, and their phone. The screens on these devices are a small amount of space in half of the world’s pocket or purse, etc.

And the screens half of the world’s population keep so near and dear to them are money spenders and money makers. My second argument is that screen is the space for consumption to get us to buy things, and the space of production to get us to do even more labor, such as clicking Yo even in the shortest of moments. In the attention economy, the push notification is the height of attention demanding and its geography is the screen. As Yo is valued of this weekend, the push notification tech of that screen geography is worth $5-10 million.

Lastly, when put together, such apps like Yo regulate the space and time of our day while making developers and mostly investors–let’s be very clear about that last group–more and more capital. In sum, the halted and manipulated spatiotemporality of life-with-app costs not only our attention but our labor and self-control. Surely the NSA and Yo keep the records of our lives, but why can’t we?

On that note, I need to go boil an egg for breakfast. I’ll be using an egg timer until I do not have to worry I’ll miss my own notification.