If All Dating Apps Are Based on Grindr, We Need to Talk about Cruising (Part I of III)

The first successful straight and lesbian dating apps emerged in the 2010s, including Tinder and HER. Widely known but woefully underexamined, these apps based their designs on, or even against, the first successful dating/hookup app: Grindr. In other words, developers imitated, refused, or even outright copied design, functionality, and structure to sell apps to straight people, lesbians, and other gay men (as the identity grouping went a decade ago, per big tech). Most importantly for my interest in lesbian, bi, queer, trans*, and sapphic (LBQT*S+) people’s experiences of dating and hookup apps, this evolution of dating apps from Grindr requires us to understand that all dating apps are based on—even by being designed alongside or against—the social and cultural hookup/dating norms of an app designed for, by, and about cis gay men, e.g. cruising.

In other words, this means that all dating apps are created from and/or against the practice of cruising.

We are way overdue to need to talk about how cruising practices’ effects are baked into dating apps. I use “baked into” as a shout to Rena Bivens and Oliver Haimson who wisely demonstrated how gender norms are baked into platforms–and sexuality and other aspects of identity are as well. I hatched these questions when designing the LBQT*S Dating & Hookup Survey, and think it would be great to dive into them together:

- Where the heck did cruising come from and why? Are cruising, anti-cruising, or something in between the actual ways of operating that people want, including gay men?

- How do gay men’s cruising norms or their antithesis still show up in Grindr, Tinder and HER? What effects might current design, functionality, and so on have for LBQT*S+ users?

- Do LBQT*S people want to embrace and/or rework practices of cruising? What are apps up against to support LBQT*S+ vs./and gay men’s cruising?

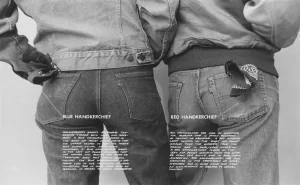

Let’s be clear about what cruising is first. Cruising can historically be understood as (usually) gay men searching for a sex partner(s) and, within a short amount of time, then having sex with that person or those people—usually casually and anonymously—in public space out of doors or in a public-private space like a dark room or bathroom of a bar. In modern times, cruising is finding someone to have sex with and, again within a short amount of time, then having sex with that person or those people—usually casual and semi-anonymous—in a public space or home. While many debate if our use of dating and hookup apps counts as cruising today, the concept, our fascination with it, and its effects haven’t gone anywhere.

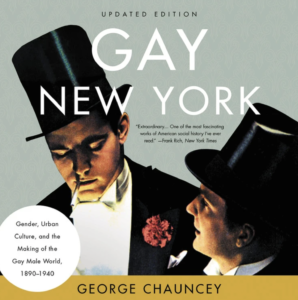

Now let’s get to the first question about what queer history can teach us. One of the first and still most important gay histories is George Chauncey’s Gay New York, which studies the lives and spaces of gay men in New York City from 1890-1930. He writes:

even anonymous participation in the sexual underground could provide men with an enticing sense of the scope of the gay world and its counter-stereotypical diversity… The sheer numbers of men they witnessed participating in tearoom sex [sex in public toilets] reassured many who felt isolated and uncertain of their own ‘normality.’ (254, cited in Race 506)

Chauncey’s brilliant and empathetic work that shows how gay men found another to not only survive but thrive in certain places and times is energizing. Notably, this is all, both literally and figuratively, steamy stuff! It’s easy to see why we keep talking, writing, and making art and more art about cruising.

But these hot rendezvous were required and not chosen. Chauncey brilliantly lays out how cruising evolved among homophobic and transphobic policies, laws, and policing of the carceral state. It wasn’t just a sexy act of rebellion—rather gay men and their hookup partners were forced into public parks, waterfronts, and the like before the advent of gay bars, many of which hosted dark rooms. The immediate assumption of some thing “untoward” or “dangerous” happening in a public space (e.g. homosexuality along with being unhoused, using drugs, doing or buying sex work, etc.) meant more policing, primarily among the already assumed “deviant” working class. And this wasn’t just New York City; it was and is everywhere.

Gay men were not able to go into a private space together like a boardinghouse or hotel so they relief on public spaces to find one another and have sex. As a result, Chauncey argues that “privacy could only be had in public“ for gay men in the early part of the 20th century. This fact will forever floor me. And, also notably: cruising clearly has some sexy and not so sexy undercurrents that are baked into our apps and queer lives.

Cruising is just one way gay men made other forms of communication, contact, relationship, and social and cultural organization to meet the limiting structures that their political economy afforded them. Would gay men have enjoyed meeting only briefly and in these abandoned and sometimes dank and dangerous spaces otherwise? Perhaps, perhaps not. The pseudo “science” that men don’t like to cuddle, like brief sexual encounters, and other such assumptions legitimate a lack of intimacy and vulnerability only serves to reassert cis-heteropatriarchal masculinities.

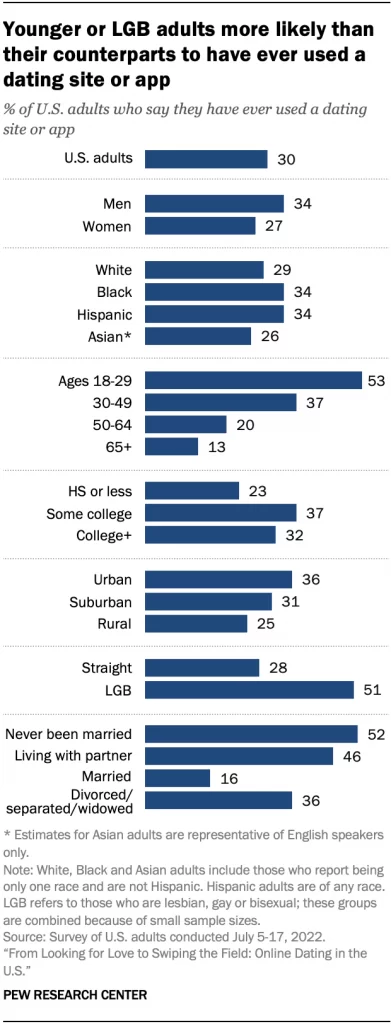

There’s so much more to learn about cruising and how homophobia and transphobia have shaped all of our gender and sexual mores. With 51% of LGBTQ US adults having used a dating app (versus 28% of straight people), we need to think about how these mores, in turn, shaped and shape queer life when we still have so few spaces in which to meet and connect openly, let alone in sexy ways. I have two more posts ahead to help us think through exactly this through together!

REFERENCES

Ahlm, Jody. “Respectable Promiscuity: Digital Cruising in an Era of Queer Liberalism.” Sexualities 20, no. 3 (2017): 364–79.

Bonner-Thompson, Carl. “‘I Didn’t Think You Were Going to Sound like That’: Sensory Geographies of Grindr Encounters in Public Spaces in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK.” In The Geographies of Digital Sexuality, edited by Catherine J. Nash and Andrew Gorman-Murray, 159–79. Springer, 2019.

Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. New York: Basic Books, 1994.

Race, Kane. “Speculative Pragmatism and Intimate Arrangements: Online Hook-up Devices in Gay Life.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17, no. 4 (2015): 496–511.